I’m happy to announce that an article I’ve been tinkering with for a little while during my day job (with the help of the infinitely patient Adam Hughes) was just published in GCN. Check it out and leave me some feedback.

Tax implications of loss or theft of Bitcoin

Hello everyone! I wanted to reproduce a post I made on Reddit earlier today. If you want to see the original feel free to check it out here. Not to belabor the point, but I’m not a tax professional, so please do your own homework and/or consult an expert before relying on this post. And with that, here’s the article:

I was reading through the instructions for IRS Form 4684 for 2014 and it seems like there are a couple scenarios where Bitcoin losses might be tax deductible. Full disclosure I’m not a tax professional or expert and you should consult your own tax adviser before filing anything or making decisions.

CAPITAL LOSS Selling trading, or purchasing goods with Bitcoin can be reported as a capital loss on Schedule D, if the fair market value on the date of sale was less than the adjusted basis. This is the standard way that most US Bitcoiners will have to report Bitcoin losses or gains to the IRS. This is also covered in depth by others who know more than me so I won’t go into more detail.

THEFT Bitcoins that were stolen from you qualify for Form 4684, providing you can prove, in accordance with IRS Pub 547, that the coins were yours and that they were stolen. For example the Coinapult theft earlier this month would seem to meet the IRS requirements for this type of loss of an individual’s Bitcoins. Proving the stolen coins were yours if the IRS questions your return is a tough but solvable issue, but I’m not really sure how anyone could prove the coins were stolen in the first place. This seems like a huge trust/credibility gap that any exchange or service has to overcome when reporting that funds were stolen. How does the IRS, or a customer for that matter, know that the wallets where the funds now reside are not also controlled by the party claiming loss? This complication makes claiming a loss due to theft a bit risky in my mind, but others may disagree.

Pub 547 also provides special rules which apply specifically to Ponzi scheme losses; however, the guidance specifically excludes mislaid or lost property from meeting the definition of a theft. This would indicate if you simply lost/erased your private keys or accidentally sent your Bitcoin to a wrong address that wouldn’t count as theft, but it could qualify as a casualty.

CASUALTY A casualty is defined as the loss of property by an identifiable event that is sudden, unexpected, or unusual. In addition to meeting the sudden, unexpected, and unusual tests, Pub 547 also addresses what factors must be proven to support the deduction of a casualty loss.

The guidance lists a bunch of deductible losses and some exceptions which are non-deductible, but few of them seem to be relevant to the kinds of situations most Bitcoiners are likely to face. If access to your private keys is cut off because a computer was destroyed due to fire, flood, earthquake, etc, that would seem to qualify as a casualty loss, as would the computer storing the keys. Also of note is that progressive deterioration and your own negligence would probably disallow you from claiming a casualty loss, so make sure to make backups, especially if the computer/phone running your wallet software is getting old or prone to data loss. This probably also means simply misplacing your private keys, or writing down a brain wallet incorrectly wouldn’t qualify for a casualty loss, though I’m not very confident of this interpretation and would love if someone with more expertise would clarify this point.

LOSS ON DEPOSITS Finally, according to the guidance, a loss on deposits occurs when a bank, credit union, or other financial institution becomes insolvent or bankrupt. One question is what would officially constitute a ‘financial institution’. I’m not sure about funds stored with non-financial services or apps like ChangeTip or Purse.IO, but it would make sense that Bitcoin exchanges would qualify.

If you lose deposited funds, you can elect to treat the loss in one of three ways: as an ordinary loss, a casualty loss, or a nonbusiness bad debt. The rules get a bit complicated here, but my reading is that a nonbusiness bad debt may only be claimed if and when the amount lost is actually known and officially determined; whereas, a casualty or ordinary loss may be elected based on estimates and before an official determination is made. Because of this distinction I think a nonbusiness bad debt cannot be claimed until a customer knows what, if any, amount of a bankrupt institution’s funds will be liquidated to cover the customer’s deposit losses. Sorry Mt. Gox creditors, you may have to wait a while if you want to elect this option.

The guidance also specifies where to report the loss of deposit based on what type of loss is elected. Ordinary losses go on Schedule A, line 23 and are subject to floor and ceiling limits. Also of note is an ordinary loss cannot be elected if the deposit is federally insured (e.g. FDIC). Casualty losses, also subject to limitations, are reported on Form 4684 and Schedule A, and nonbusiness bad debts go on Form 8949 and Schedule D.

So that’s basically my reading of IRS guidance as it relates to the deductibility of Bitcoin losses. Again, I’m not an expert or a tax professional, but I’m interested to hear your comments, corrections, and input. Feel free to check me out on Twitter. Thanks!

Digital Currency Course Essay Series: Seventh Essay (ASICs and future price uncertainty)

Another long-awaited post! This time traveling for the day job got in the way. Oh, for a day when I can turn this crypto-hobby into an independently profitable venture… Maybe this is a good time to plug my donation address? If you dig my stuff, please send a few Satoshi to 13FHYdAjkKJXHuiAHNyoHNybEn7yRHrfum. Also see here for other essays related to the University of Nicosia’s MOOC on Digital Currencies.

Essay 7 Prompt: Bitcoin ASICs are pushing the limitations of manufacturing. Where do you believe this could lead given the uncertainty of the future exchange rate ? What could this mean for mining in the mid-term future?

ASIC miners are orders of magnitudes more efficient and effective at running the Bitcoin hashing algorithm, making them by far the most (and perhaps the only) profitable mining hardware setup at present. ASIC miners achieve this superior efficiency by pushing the limits of our current technologies, designing an integrated circuit with the specific configuration most efficient for the relevant Bitcoin mining functions. As a consequence of a direct profit motive to reward improved hardware performance, ASICs represent the apex of mining hardware. The peak, that is, as constrained by certain current technology, for example the density of logic gates, computer cooling technology, and design efficiency of industrial mining farms. The potential for exponential returns from revolutionary advances in mining technology will continue to provide incentives to engineer a better Bitcoin miner, and in a year or a decade we could be debating the impact of the new technology on the formerly ASIC-dominated mining sector.

Over the long-term, the supply of ASICs will continue to increase until competition for blocks and the resulting burgeoning block difficulty pushes the expected value of associated block rewards equal to the marginal cost of an additional miner. Uncertainty in the future price of Bitcoins complicates miner’s calculations in the short- and mid-term, however. If the price of Bitcoin were to double tomorrow, perhaps additional mining rigs bought today would be profitable. On the other hand, if the price were to halve, miners might find an ASIC bought today to be a bad investment. Therefore, future price uncertainty may lead a bullish mining sector to over-invest, and go broke; whereas, a needlessly bearish mining sector might hesitate to invest in additional capacity at the peril of mining efficiency. Therefore, with a more certain future Bitcoin exchange rate, the deployment of mining hardware would bend towards ideally efficient levels.

Digital Currency Course Essay Series: Sixth Essay (Centralization of mining pools)

And I’m back! with another essay from the University of Nicosia’s Digital Currency MOOC after a brief hiatus. I haven’t posted as frequently due to a couple lectures lacking essay prompts and my falling a bit behind in the MOOC to attend the Bitcoin in the Beltway conference in downtown Washington, D.C. (my backyard and former home). I may try and write a post on the conference before too long, though I have more of the MOOC to catch up on as well. As always, you can find the rest of the Digital Currency Course Essay Series here.

For this essay, the prompt was: Recently and according to this distribution, Ghash.io has (again) concentrated a very sizeable percentage of the hashing power of the network. Why is this happening and how could it be avoided to prevent a potential “51% attack”?

Ultimately, Bitcoin mining is a business, and mining operations that are run like a successful business are the ones that will survive, earn better profit margins, and be able to reinvest those profits in expanding and improving hardware. The centralization of pluralities of Bitcoin hashing power in just a few mining pools is a natural consequence of the business conditions that mining pools lay out before potential new pool members. This comparison of Bitcoin mining pools on the Bitcoin wiki has a handy chart showing selected data about various Bitcoin mining pools, although the chart is a bit dated and does not contain information on some of the larger players currently on the scene (such as Discus Fish), it will nonetheless help illustrate some key points.

First, note that in the data, there are only 9 pools with hash rates of at least 100 TH/s: BitMinter, BTC Guild, Eclipse Mining Consortium, Eligius, GHash.IO, Multipool, P2Pool, PolMine, and Slush’s pool. Of these top 9, only 1 pool, EMC, keeps the transactions fees associated with a correct block. The other 8 pools all share transaction fees proportionally with miners, along with the block reward. Transaction fees are currently dwarfed by the block reward: fees currently total approximately 11 bitcoin per day (according to Blockchain.info); whereas, the block reward churns out a staggering 25 bitcoin every 10 minutes. Over time as the block reward halves again and again, transaction fees will become a more important incentive for miners and the pools that greedily withhold transaction fees from their constituent miners will find it increasingly harder to maintain a significant share of mining power.

Going back to our comparison of pools on the Wiki, we note that fees charged by pool operators are another key distinguishing factor. Five of the nine largest pools advertise either 0% fees for payment of shares or issue promises of no other fees, and GHash.IO, the largest pool, advertises both. One other mining pool, PolishPool, offers no PPS fees and promises no other fees. According to the ranking, PolishPool only has about 5 TH/s hashing, but language barriers may account for much of that variance. Here again, miner’s rational self interest of maximizing profit tends to centralize Bitcoin mining on the pools that promise to take the smallest cuts out of rewards for successful block creation.

Since we have identified the cause of mining centralization as a few pools offering superior pricing schemes, the solution to centralization logically follows. More pools should consider lowering their fees and offering to share transaction fees. This would lessen the economic motivation towards centralization. Of course, this is easier to articulate than to implement since mining pools also incur costs to operate and therefore must charge some fees as a going concern.

References:

1. Bitcoin Wiki, Comparison of mining pools

https://en.bitcoin.it/wiki/Comparison_of_mining_pools

2. Blockchain.info, Total Transaction Fees

Digital Currency Course Essay Series: Fifth Essay (Centralized asset or transaction ledger)

This is the final essay for lecture two (the Byzantine Generals Problem) of the University of Nicosia MOOC, Intro to Digital Currencies. This prompt asked students to describe a centralized asset or transaction ledger and describe advantages or disadvantages of decentralizing the ledger. I must admit, I might have stretched a bit in my example selection. Nonetheless, I’m proud of this one and I think the analogy is interesting and useful, if unlikely or a bit silly. This and all the essays are all tagged: Digital Currency Course Essay Series.

Prompt: Describe a centralized asset or transaction ledger and describe what advantages or disadvantages might exist if it were to be implemented in a decentralized form.

This might be a little out there, but I have to admit I peeked at the everyone else’s responses to avoid picking a popular example of a centralized ledger. The example of a centralized asset ledger I’ve selected is YouTube.com’s database of available videos. Currently, to add an asset to the ledger, a YouTube user must first create or sign in to an existing account with Google. The user uploads the video to YouTube’s servers, and software updates the database with information about the video, such as what account submitted the video, a timestamp, whether the video is marked public (searchable and all may view), private (only viewable by accounts specified by the uploader), or unlisted (not searchable but anyone with the link may view), among other data. Assets may be removed from the ledger by several methods: YouTube staff will delete videos that violate its terms of service or as a result of a successful Copyright Infringement Notification, and the user who submitted a video may also mark it for deletion. Once the deletion is effected, the video may no longer be viewed nor the deletion reversed; however, the YouTube Terms of Service, section 6C, state, “you understand and agree, however, that YouTube may retain, but not display, distribute, or perform, server copies of your videos that have been removed or deleted”, so the content may still exist on the YouTube servers.

In a decentralized model of the database of YouTube videos, users might post content to a self- or decentrally-owned site and submit a link to a blockchain-like ledger of submitted videos. The blockchain software might visit the link to validate that a video exists and trace prior confirmed submissions to ensure the same link is not already included in the ledger. The uploading user may also be required to prove that she has the ability to manage the linked content.

There are several advantages and disadvantages that might arise by converting YouTube’s database of video submissions to the decentralized model described above. Firstly, with a decentralized ledger, it would be impossible to remove the initial link submission, as the ledger must be public and prior additions unalterable in order to function and foster trust in the system. A user could remove or change the content from the linked site; however, the entry of the link in the ledger would still persist in the history of asset additions. This feature has advantages, for example, it would be the individual users’ responsibility to comply with copyright law as opposed to leaving this right in the hands of the central managing authority (i.e. Google). One could also imagine scenarios where the inability to truly remove record of the link could be disadvantageous, such as if the content is viral and politically unpopular. Taking the maintenance of the ledger out of a single entity’s hands does have clear advantages in that searching for content could be vastly improved, and there is no risk that the central manager fraudulently alters data relating to the video, such as timestamp or the submitting user. Furthermore, data about uploaded videos would be visible to all instead of trusted to a single entity, and with multiple nodes maintaining full copies of the ledger, a denial of service attack on the database would be exponentially more difficult.

Although unorthodox, a decentralized asset ledger of uploaded video content might prove advantageous over the centralized model employed by Google’s YouTube.com.

References:

1. YouTube.com, Video Privacy Settings

https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/157177?hl=en

2. YouTube.com, Terms of Service

Digital Currency Course Essay Series: Fourth Essay (Proof of work)

This next essay in the Digital Currency Course Series is the first one I wrote for the second lecture taught in the University of Nicosia’s Bitcoin MOOC. This chapter is about the Byzantine Generals Problem and the theoretical underpinnings of Bitcoin.

Prompt: Describe in your own words, why ‘proof of work’ is important to a decentralized blockchain-based system like Bitcoin.

For any ledger to be trusted, the users must be assured that the transactions comprising the ledger are valid, authorized, and represent actual transactions that have occurred. In the case of a centralized ledger, all the transactions are entered by a single, trusted authority, such as a bank or a company’s accounting department. In many cases, this trusted authority will also hire a disinterested third party, such as an auditor or public accountant, to review the ledger and the transactions that comprise it and attest to the veracity of the data.

In the decentralized ledger model, the trusted authority is done away with, and instead, many disbursed entities may submit transactions to be recorded to the ledger. Therefore, in order to assure participants that the ledger can be trusted, a decentralized system must have rules which govern the posting of items to the ledger. Bitcoin and other alternative cryptocurrencies have chosen ‘proof of work’ as the governing rules for posting transactions to the blockchain ledger (as an aside, some people have proposed other systems, such as proof of stake, as an alternative set of rules to govern transaction posting). Proof of work requires a user’s computer to expend effort and resources as the price for posting transactions to the blockchain. The bitcoin protocol demands that a computer discover a nonce, a string of garbage data, which when combined with the transaction details and run through a cryptographic hash function, produces an output value which meets certain difficulty criteria. The bitcoin software adjusts these criteria accordingly as the pool of computing power dedicated to searching for a solution waxes or wanes. Users are allowed to post transactions to the blockchain only after exerting the time, effort, and resources to find a correct solution, and because the effort level required is kept consistently high, the probability of discovering a solution is fairly low relative to the resources that must be invested. Consequently, any person wanting to examine the blockchain can be assured that transactions are not frivolously posted and that there is some degree of network security. Combined with rules governing what constitutes a valid transaction, the proof of work system gives bitcoin a level of security and reliability on which trust can be built and users can be assured about the accuracy of the blockchain.

References

1. Bitcoin Wiki, Protocol rules

Digital Currency Course Essay Series: Third Essay (Functions of currency)

Here is the third and final essay for the University of Nicosia MOOC on cryptocurrency’s first lesson, Introduction to Digital Currencies. My other responses can be found here.

The prompt: Post 2-3 paragraphs comparing any two types of currencies along the dimensions of the functions of currency and rate their pluses and minuses in this regard.

Currency is useful in an economy by performing three primary functions, as a medium of exchange, a store of value, and a unit of account. The functions are independent but mutually reinforcing, and different types of currencies perform each function better or worse than other currencies. The advantages and disadvantages between primitive, commodity currency and paper fiat money strongly illustrate this concept.

As a medium of exchange, a currency is a common intermediary which allows for a standard comparison of value between diverse types of assets for trade. Without media of exchange, sellers are forced to accept as pay for their wares only items their suppliers might accept in trade, a type of transaction cost known as a double coincidence of wants. As a medium of exchange paper currency is superior to commodities across many dimensions. Paper money is highly fungible and divisible since each note is consistent with the next and multiple notes of varying denomination are typically issued. Contrarily, the fungibility and divisibility of different commodities might be greater (one kilogram of salt) or lesser (one cow). Furthermore, paper money is generally easier to transport than most commodities, further enhancing its value as a medium of exchange.

A good store of value permits individuals to retain wealth over a period of time with a measure of predictability about the asset’s future worth. The supply and demand, as well as expectation about future supply and demand, all affect the value of a currency, whether commodity or paper. Many commodities used as a currency have some inherent utility and therefore floor on demand; whereas, the demand for paper money is generated solely by its use as a currency. The supply of commodities may experience a sudden shock if a new reserve is found or a big cache is destroyed. On the other hand, the supply of paper money is generally determined by a central bank or other sovereign authority. The predictability of future value varies widely among paper and commodity currencies, so neither is inherently more advantageous as a store of value.

A unit of account allows for a standard measure of the worth of disparate assets, liabilities, and economic activities. Deflating money leaves its holders better off just as Inflation in a currency may benefit holders of debt denominated in the currency; however, up and down movement in the value of paper money or commodities complicates the comparison of the currency across time. The utility of a currency as a unit of account depends less on whether it is paper money or commodity than it does on the form of paper money or the particular type of commodity.

Digital Currency Course Essay Series: Second Essay (Benefits of a decentralized currency)

I have the first three essays already finished, so I’ll go ahead and publish them all now. In the future, I’ll post the essays as I write them so they will appear here a bit more sporadically, though that’s probably a feature, not a bug. Anyway, onward we press, to essay number two.

Prompt 2: post research and mention your opinions on why a decentralized currency may have benefits over a centrally issued one for private issuers.

There are a couple as yet unmentioned advantages that a decentralized private currency might have over a centralized one:

First, and perhaps most importantly, since privately issued currencies compete to some extent with money sanctioned by sovereign states with court systems and law enforcement agents, decentralized private monies are more resilient to legal attacks and other forms of pressure than are centrally-issued currencies. Case in point is E-Gold, an early internet payment service provider, operated by Gold & Silver Reserve, Inc (G&SR) and initially backed by gold reserves in safe deposit boxes. After changes to money laundering standards promulgated in the USA PATRIOT Act, E-Gold and G&SR faced various allegations and legal attacks, including unlicensed transmission of money. The owners plead guilty, sentences were issued, and millions of dollars in assets were seized. Further, Paypal has notoriously been subjected to pressure from the U.S. government, such as State Department lobbying to freeze donations to Wikileaks. In the world of Bitcoin, exchanges have been a single point of failure and have been subject to hacks, legal action, and other attacks. Distributing issuance makes the currency less vulnerable to attacks on one node; instead, most or all of the network must be compromised to shut the currency down.

Second, by its nature a currency whose issuance is disbursed rather than concentrated must have rules and procedures for the issuance of additional units of the money. If anyone could issue the currency at any time, inflation would run rampant and the currency’s value would plummet. Bitcoin solves this problem with mining, a proof of work system, monetary policy built into the protocol, and the open source and transparent nature of currency issuance, among other innovations. These rules and systems make the issuance of new Bitcoin highly predictable, which is generally good for markets and efficient operation of businesses. Centralized private currencies, however, need not follow published, predictable rules for currency issuance. The “central bank” of the currency may be staffed by extremely intelligent, wise, and trustworthy individuals, or it may not. The babysitting co-op case study presented in the additional reading to the course articulates how first a recession, then a depression in the market for babysitting scrips was created by the monetary policy of the co-op board, not due to malfeasance, just ignorance and a poorly designed economy. According to Wikipedia, the wisdom of the crowd theory states that a “large group’s aggregated answers to questions involving quantity estimation, general world knowledge, and spatial reasoning has generally been found to be as good as, and often better than, the answer given by any of the individuals within the group.” If this holds true to the issuance of private currency, then the decisions made by consensus in a decentralized environment should tend to outperform ones made by a central authority.

References

1) Wikipedia.org, E-Gold

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/E-gold

2) Digital Currency Business E-Gold Pleads Guilty to Money Laundering and Illegal Money Transmitting Charges

http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/2008/July/08-crm-635.html

3) Operation Payback cripples MasterCard site in revenge for WikiLeaks ban

http://www.theguardian.com/media/2010/dec/08/operation-payback-mastercard-website-wikileaks

4) The Bitcoin drama continues: another exchange shuts down, while Overstock reports over $1 million in Bitcoin sales

http://www.engadget.com/2014/03/04/another-bitcoin-exchange-shuts-down/

5) Bitcoin.org, Frequently Asked Questions, How are bitcoins created?

https://bitcoin.org/en/faq#how-are-bitcoins-created

6) Monetary Theory and the Great Capitol Hill Baby Sitting Co-op Crisis: Comment

http://cda.morris.umn.edu/~kildegac/Courses/M&B/Sweeney%20&%20Sweeney.pdf

7) Wikipedia.org, Wisdom of the crowd

Digital Currency Course Essay Series: Intro + First Essay (Describe your local currency)

As previously mentioned, I’m enrolled in the University of Nicosia free MOOC on digital currencies. One of the assignments for each lecture in the course is to write a brief essay for each of a couple topics related to the material covered in that lecture. To encourage myself to put more effort in my responses and gather feedback from readers not necessarily enrolled in the course with me, I’ve decided to publish each of my responses as a separate post on this site. I’d love your feedback, whether you like what I wrote or not. Without further ado, here’s the first of my responses.

The prompt is: post a short paragraph, describing your local currency and how potential changes in its supply or demand you are aware of, have affected its exchange rate over a timeline you choose.

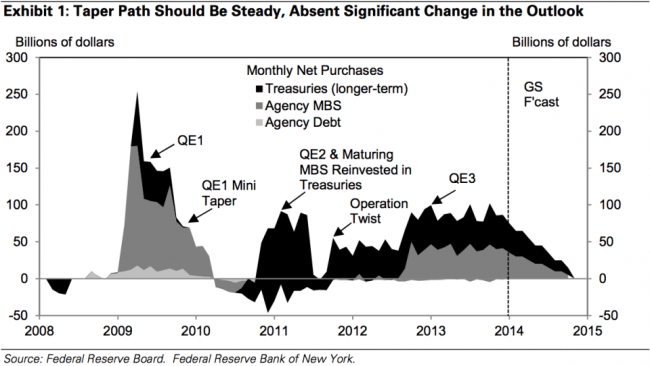

My local currency is the United States Dollar, a sovereign form of fiat money, centrally issued by the U.S. Federal Reserve and used more often in international transactions than any other currency. In late 2008, the Fed began a monetary policy called quantitative easing, injecting dozens of billions of additional dollars into the circulating money supply each month. This chart shows the total value of dollars put into circulation through quantitative easing from 2008 through the present, with a projection of future activity through 2015:

The next chart shows, after accounting for the effects of quantitative easing, the total base money supply (M0) of U.S. Dollars in circulation from January 2009 through the present (in millions of dollars):

The currency I have chosen to compare against the Dollar is Bitcoin. First mined in early January 2009, Bitcoin is a private, decentralized, digital cryptocurrency which, unlike the U.S. Dollar, has a fixed total supply (21 million Bitcoins to be mined by circa 2140), which is fabricated according to an open source Bitcoin generation algorithm. Accordingly, the total money supply of Bitcoins in circulation has smoothly increased from zero on January 1, 2009 to approximately 13 million today:

If we compare the quantity of Dollars and Bitcoins in circulation across the selected time horizon, we see that the supply of Dollars in January 2009 was approximately 1.70 x 1016 whereas the supply of Bitcoin was near 1. Presently the supply of Dollars has climbed to nearly 3.93 x 1016 and Bitcoin has risen to 1.28 x 107. Over the past four years, the supply of Bitcoin has increased exponentially; whereas, Dollars have merely doubled. Therefore, all else being equal, we should expect the price of Bitcoin relative to Dollars to have plummeted in the past four years. Of course that expectation is not reflected in reality:

The preceding graph shows the price of Bitcoin in Dollars over the past five years. From the data, the price looks fairly stable until a first, small blip and downswing around May 2011, a larger jump and softening of price May 2013, and a last dramatic spike cycle this past December. So given what we know about the supply of these two currencies, why is a Bitcoin now trading near $450 dollars when January 2009 it was worth mere pennies?

As a new currency Bitcoin has certainly been very volatile since its inception, a quality that will hopefully subside as Bitcoin grows older. However, volatility could account for erratic price movement but would not explain the upward trend, especially given the disparity in rates of inflation of Bitcoin relative to Dollars. I believe that the upward price trend is best explained by changes in relative demand, as well as current expectations of future demand.

In the past five years, the number of individuals and businesses willing to accept Bitcoin as tender has grown considerably. Furthermore, the expectation about the future of Bitcoin has grown immeasurably more positive since 2009. Therefore, I believe, relative to the U.S. Dollar, the burgeoning demand for Bitcoin since 2009 has offset the rising supply and this growing demand accounts for the increasing price of Bitcoin.

Sources:

1) A Complete History Of Quantitative Easing In One Chart

http://www.businessinsider.com/quantitative-easing-chart-2014-1

2) United States Money Supply M0 [2009 – 2014]

http://www.tradingeconomics.com/united-states/money-supply-m0

3) DFIN-511 Introduction to Digital Currencies, Session 1: A brief history of money

4) Total Bitcoins in Circulation [All Time]

5) Market Price (USD) [All Time]

Welcome to BlakeChain!

Thank you for visiting BlakeChain! This is my all-in-one site for cryptocurrency news, ideas, discussion, questions, learning, and interaction. I’ve got lots of ideas for articles to write, and I’ll begin posting them as I have time. I’m currently enrolled in the University of Nicosia MOOC on crypto, and I’m planning to post my articles for the class as individual posts here. In the spirit of the open source nature of the Bitcoin community and this interesting Daniel Krawisz post on the correct strategy for Bitcoin entrepreneurship, I will also be discussing ideas I have for Bitcoin and blockchain related businesses, services, and other content.

Please follow me on Twitter, @BlakeChain. I’m going to look into wallets that generate a unique public key address for each post, but for now, you are all spared the donate spiel. Though if you are desperate to throw a few BTC my way, you can find a donation address on my Twitter profile. Feedback is welcome and the best way for me to make the site better, so please ping me here, on Twitter, or directly at blakechain@gmail.com.

Thanks, and enjoy!